A Purple Heart, 59 Years Late:

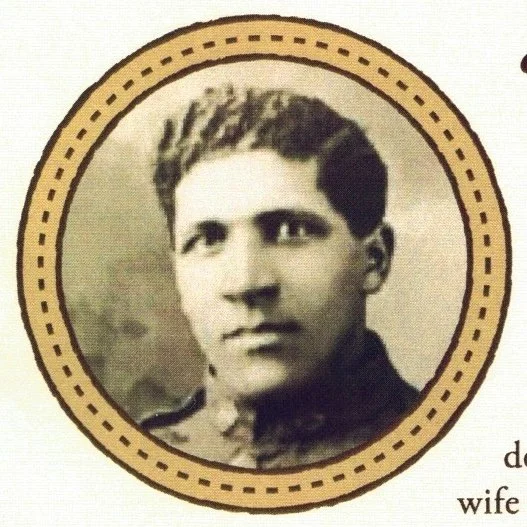

The Story of ralph logan

A Veteran’s Day Tribute

In 1917, a 25-year-old Black man named Ralph Logan left his family's ranch in Palo Cedro, California, to serve a country that didn't yet see him as fully equal. He was assigned to the 365th Infantry—one of the segregated "Colored" units—and shipped to France to face the mechanized horror of the Great War.

In the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, German artillery shells delivered something Ralph couldn't see, couldn't fight, couldn't outrun: mustard gas. The chemical weapon tore through his lungs, searing tissue, leaving wounds that would mark him for life.

Injured and eligible for treatment, Ralph was sent to a rear-line aid station. But he didn't stay.

He walked out.

Years later, he would explain simply: "I was never so glad to get out of a place in my life." The suffering he witnessed—men with limbs torn away, faces destroyed, bodies broken beyond recognition—made his own wounds seem "kind of small." So he left, returning to the front lines rather than be surrounded by the unbearable evidence of what war does to human beings.

This was Ralph Logan: a man who minimized his own pain in the face of others' greater suffering.

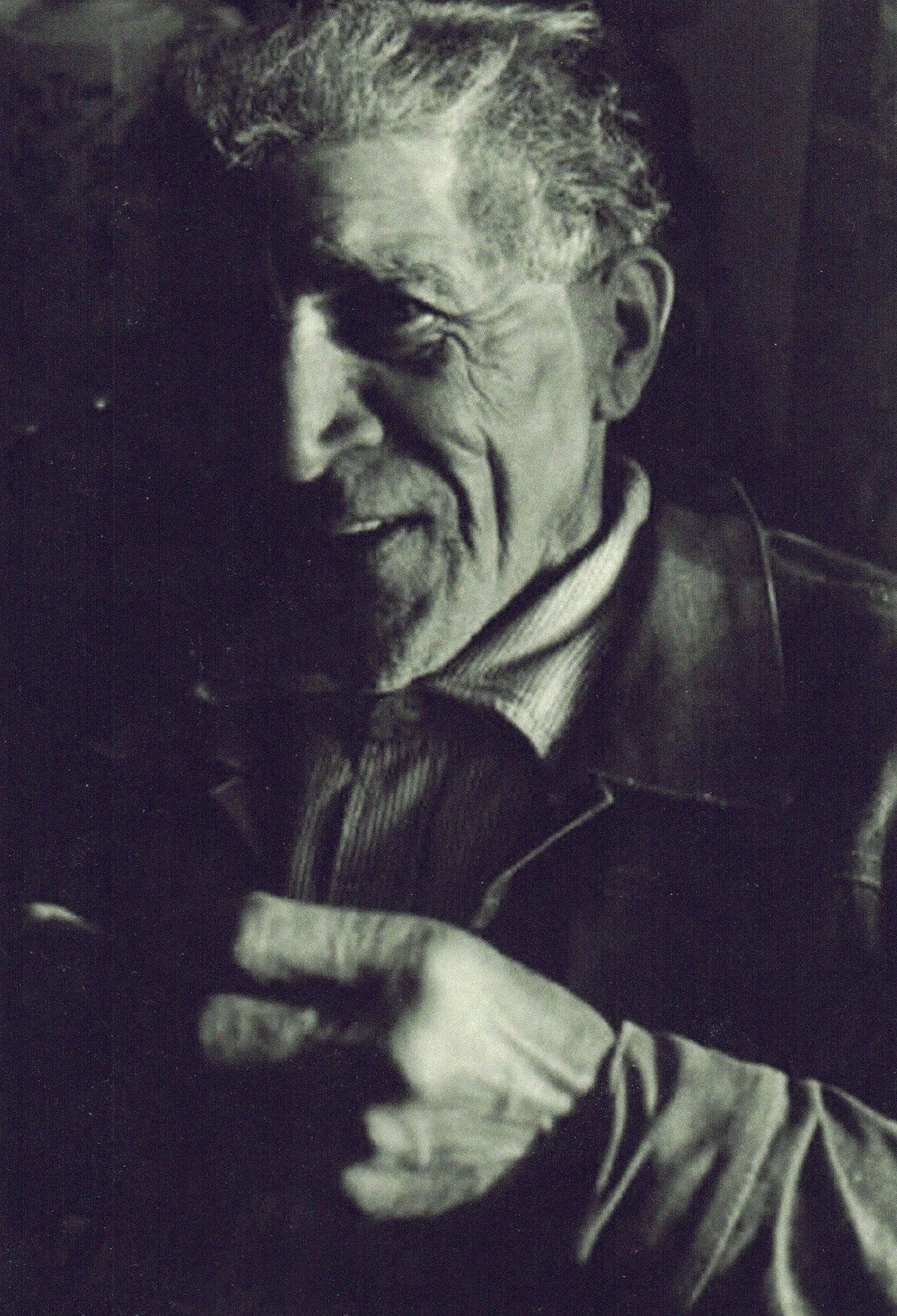

After the war, Ralph returned to Northern California and to the work he knew best: raising cattle on 350 acres of rolling ranch land with his brothers. He lived quietly, carried his war wounds privately, and built a life filled with what one local article described as "understanding and kindness." His friends, the article noted, "are numerous and come from all walks of life."

The Army had forgotten him. Or perhaps, more accurately, had never properly seen him in the first place.

For 59 years, Ralph Logan lived without the recognition his service had earned. No Purple Heart. No acknowledgment that he had bled for his country in the fields of France.

Until 1977.

A local politician learned that this elderly Black veteran—now 85 years old—had never received the medal he was due. He brought it to the attention of the proper authorities. And finally, nearly six decades after Ralph Logan walked through mustard gas for America, the Army, Air Force, and Marine recruiters marched across his backyard in Palo Cedro to pin his Purple Heart on his striped work shirt..

Can you imagine that moment? An 85-year-old man, standing on the land his father had built, watching uniformed servicemen cross his property to finally, finally, say: "Thank you. We see you. Your service mattered." With quiet dignity, Ralph simply said, “Thank you.”

Ralph Logan's story isn't just about military service. It's about dignity maintained in the face of indignity. It's about character that doesn't demand recognition but quietly deserves it. It's about a Black man who served a segregated military, survived the worst humanity could devise, minimized his own suffering, built a life on the land he loved, and waited with grace for acknowledgment that came 59 years too late.

This Veteran's Day, I think about my great-uncle Ralph Logan. I think about the thousands of Black veterans whose service went unrecognized, whose sacrifices were minimized, whose Purple Hearts came late—or never came at all.

And I think about what he represents: the insistence on dignity, the quiet heroism of returning to ordinary life after extraordinary trauma, the refusal to become bitter even when the world doesn't give you what you've earned.

Ralph Logan's life, like the keys on a piano, spanned both the black and white notes of American history. He played his part with grace, with character, and with the kind of humanity that makes you walk out of a hospital because others are suffering more than you are.

That's the kind of veteran—the kind of man—worth remembering.

Ralph F. Logan (1892-1981) was born near Cottonwood in Northern California, at the mouth of Bear Creek. He was the son of Richmond and Lilla Ellen Bowser Logan. His father operated Logan's Ferry, which later became Balls Ferry, and built the Sixteen-Mile House stage stop. Ralph served in the 365th Infantry (Colored) during World War I and was wounded by mustard gas in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. He received his Purple Heart in 1977, 59 years after his service.

He grew up alongside his brothers Ernest and Clay in a family rooted in the ranching traditions of Tehama and Shasta Counties. Pleasant Dixon Logan, Ralph’s

grandfather, was a Quaker of Scottish Irish descent. He had journeyed west in the 1860s with his “Negro wife” Cynthia and their children, settling in California after crossing the plains in a covered wagon. From those pioneer beginnings, the Logan family became deeply involved in cattle raising, farming, and local enterprise.

By 1907, Richmond Logan moved his family to Palo Cedro, where he began his own cattle venture. The Logan boys were strong, hardworking and deeply familiar with ranch life, but Ralph chose to remain on the 500-acre ranch for the rest of his life. His formal schooling was short-lived as he much preferred the open range to the classroom. Donning a broad-brimmed hat, boots, and leather cuffs, Ralph embraced the cowboy life. Summers were spent driving cattle into the Lassen National Forest and Montgomery Creek. He gained a reputation as a skilled horseman, frequently participating in rodeos and breaking horses for use on the ranch an beyond.

Ralph Logan passed away in 1981 and was laid to rest in Redding, California, beside his parents and siblings. Shortly afterward, his beloved wife Gladys also passed. Ralph’s legacy continues through his four grandchildren, ten great-grandchildren, seven great-great-grandchildren, and his nephew, Emanuel Logan Williams.

On October 16, 2025, Ralph Logan was posthumously inducted into the National Multicultural Western Heritage Museum’s 21st Annual Hall of Fame.

This story is part of the Logan family legacy explored in "Black and White Piano Keys" - a memoir about race, family, music, and the complex harmonies of American life.